This is the content from my article in the Pellet Mill Magazine published Dec. 11th 2019.

The potential of combined-heat-and-power plants, especially with organic Rankine cycle, can turn the tides in favor of biomass as a key part of Germany’s energy transition.

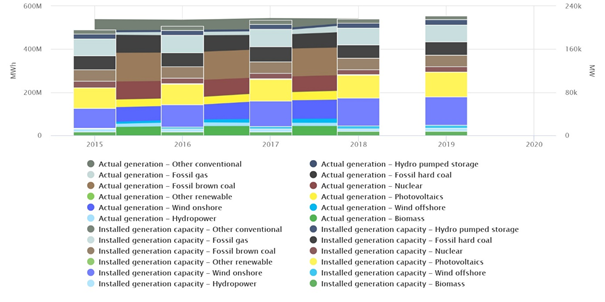

The German Renewable Energy Act (EEG) of 2000 succeeded in boosting development of renewable energy such as solar and wind power. The feed-in tariffs guaranteed a fixed income for electricity producers, thus attracting investors, and helped the industries grow exponentially. In late September, Germany published the new Climate Package. The goal is a reduction in CO2 emissions by 40% by 2020 compared to 2009, and by 55% by 2030. With such ambitious targets, it might be assumed that Germany implemented a biomass cofiring strategy, too. However, that’s not the case.

While other European countries such as the U.K., Netherlands, Belgium and Denmark subsidize cofiring, Germany is lacking feed-in tariffs for wood pellets and other biomass in coal plants.

Additionally, the CO2 price (EUA-Future)—an important lever for substituting fossil fuels with renewable energies—averaged the past 12 months at approximately 25 euros per ton (EUR/t). Experts point out the price for CO2 certificates should range between 50 and 130 EUR to be effective. The German Climate Package, however, sets the price at 10 EUR/t from 2021, with a systematic increase to 35 EUR/t by 2025. Unfortunately, this strategy does not support cofiring of biomass in coal power plants at all. If it did, demand would be substantial: At a cofiring ratio of 10%, Germany’s demand for wood pellets would exceed 7 million tons annually.

CO2 Mitigation Potential is Considerable

There is another problem. In 2012, about 150 plants globally operated using cofiring to reduce CO2 emissions, 30 of them in Germany. Yet, only 13 biomass power plants operated permanently, mainly with sewage sludge and waste materials. At the same time, the efficiency of conventional, subcritical pulverized coal-fired power plants was 36%, state-of-the-art coal power plants had an efficiency of 46%, and biomass power plants 25%.

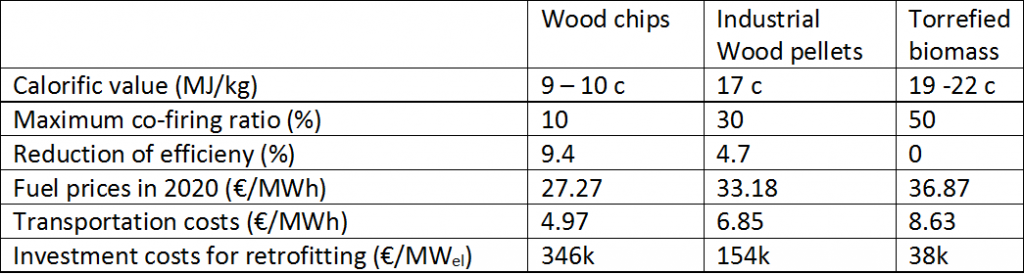

Since 2012, the efficiency of biomass-fired power plants has improved from 25% to 36%, whereas state-of-the-art coal-fired power plants average 49% efficiency. Cofiring wood chips and wood pellets leads to a slight decrease in efficiency. Nevertheless, using torrefied biomass does not lead to an efficiency decrease, as it has comparable properties to coal. The main advantage of cofiring biomass is that it leads to up to 50% reduction in CO2 (7% with wood chips, 36% with industrial wood pellets and 50% with torrefied biomass). However, the total cost of cofiring significantly differs.

Cofiring wood chips leads to the lowest CO2 mitigation costs, but the investment costs for retrofitting a coal plant are substantial, the cofiring rate is limited, and thus, the overall CO2 mitigation potential is limited. Torrefied biomass, on the other hand, has a high cofiring rate and low retrofit investments. But due to high fuel prices and transportation costs, CO2 mitigation costs are substantial. Therefore, use of industrial wood pellets seems to be the most advantageous option, though all three cofiring options require subsidies or a higher CO2 certificate price.

Nothing New in Germany’s Biomass Power

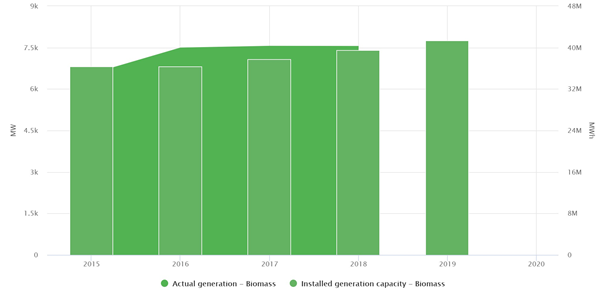

The installed capacity and the actual electricity generation from biomass reflects the situation in Germany. In 2015, the installed biomass electricity capacity was 6,808 MW with an actual electricity production of 34,850 GWh (6.5% of total electricity production). In 2019, the installed capacity increased by 14% to 7,752 MW (with actual biomass electricity production in 2018 being 40,184 GWh, (7.45% of total electricity production). The share of biomass in Germany’s total electricity capacity did not substantially increase from 2015 (3.47%) to 2019 (3.48%) and remains marginal. (Federal Network Agency, SMARD, 2019.)

Besides the missing EEG feed-in tariff and a low CO2 price, the most important barriers to cofiring biomass in Germany are the uncertain availability, a wrong interpretation of biomass in terms of energy use, and the already increased competition in the power market. With at least seven million tons of wood pellet demand when cofiring 10%, Germany’s risk of lack of supply is very high. Long-term contracts as seen in the U.K. could help de-risk the supply side. On the governmental side, there is a need for rethinking use of biomass in the power sector. Currently, cofiring biomass is led by waste and sewage sludge, and there are high licensing requirements. Biomass from wood chips and wood pellets would need to be treated differently than waste to reduce the licensing hurdles. Finally, German energy producers are still struggling with the nuclear power phase-out.

A study of Germany’s Energy Agency assumes that German coal plants could cofire up to 50% wood pellets without significant modifications to the existing equipment. Determined steps by German policymakers are necessary to benefit from CO2 mitigation potentials cofiring with biomass holds. The potential of combined-heat-and-power plants, especially with organic Rankine cycle, can turn the tides in favor of biomass as a key part of Germany’s energy transition.

References:

Lüschen, A. / Madler, R., Economics of Biomass Co-Firing in New Hard Coal Power Plants in Germany, FCN Working Paper No. 23/2010.

Knapp et al., Energy, Sustainability and Society (2019), https://doi.org/10.1186/s13705-019-0214-3

Roni et al., Biomass co-firing technology with policies, challenges, and opportunities: A global review, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 78, 2017, p 1089 – 1101.